This blog addresses a paradox: why is it that the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR or ‘the Court’) continues to be the target of vituperative rhetoric from UK ministers and others, when the number of judgments against the UK has steadily fallen and the UK (as a successful respondent state) has been a beneficiary of the “age of subsidiarity” proclaimed a decade ago by the former President of the Court, Judge Robert Spano?

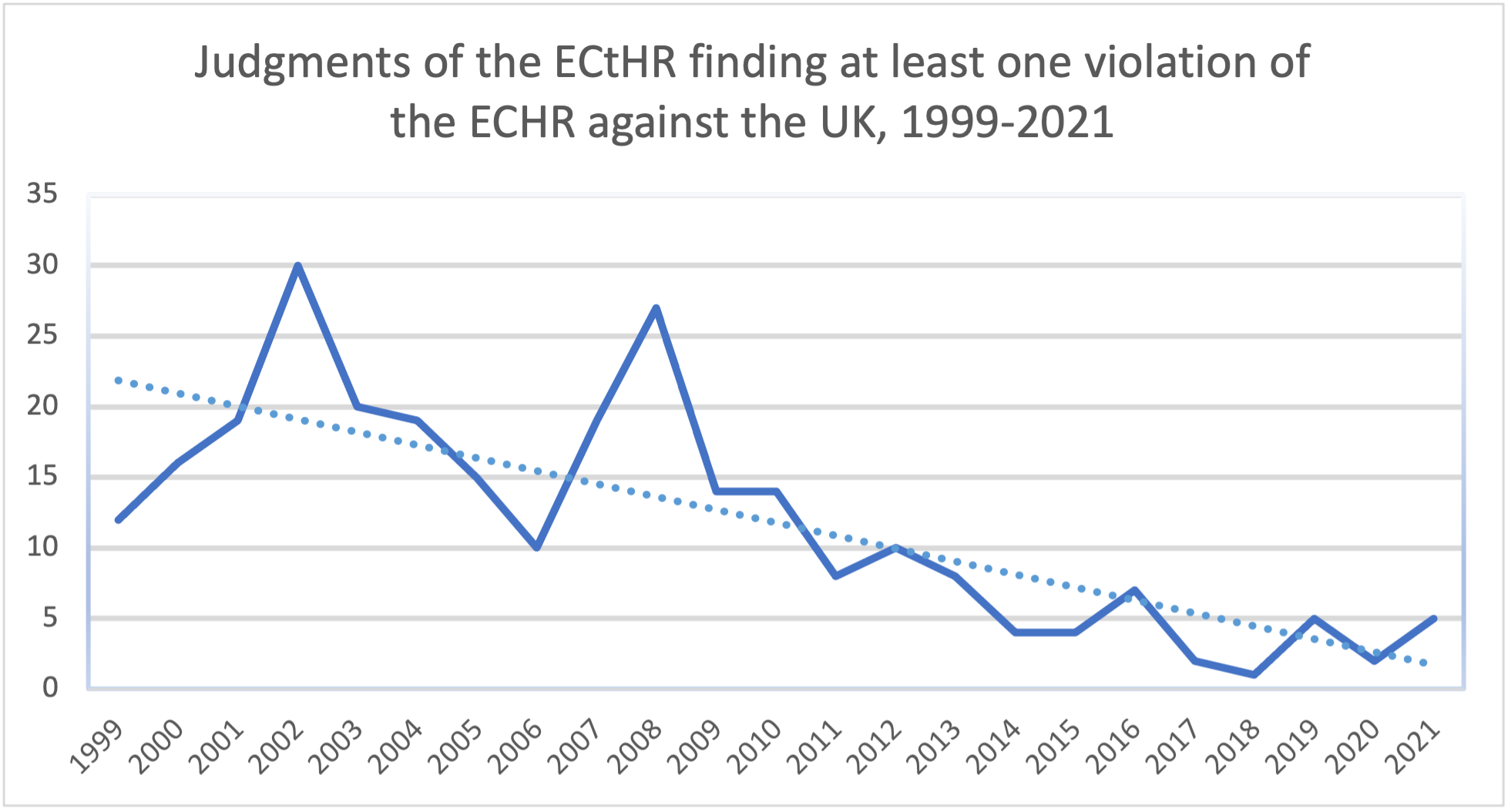

When the Human Rights Act 1998 was passed, and human rights were “brought home”, the expectation was that the number of judgments finding violations against the UK would decline. And so it has come to pass. As shown below, the average number of violation judgments per year in the past decade (2012-2021) was fewer than five, whereas the average for the preceding decade (2002-2011) was almost 18.

This fall reflects the fact that, as the HRA intended, courts and other public authorities in the UK now consider human rights more intensively and explicitly than before—and the ECtHR is, in turn, more likely to endorse their reasoning and conclusions.

Unravelling the paradox

But here we encounter the paradox, because although the Court has issued progressively fewer judgments that might irk ministers, portrayals of Strasbourg as unduly meddlesome persist. In recent months, Richard Ekins asserted that the UK needs to be “freed” from the jurisdiction of the Court, which “routinely subverts” the terms of the European Convention on Human Rights, while Home Secretary Suella Braverman accused Strasbourg of having “centralised power” and of “pursuing an agenda which is at odds with our politics and our values”.

Such perceptions contradict not only the data, but also the ECtHR’s direction of travel, set notably by Judge Spano who wrote in 2014 about a new “age of subsidiarity”. He was directly responding to the Brighton high-level conference on the future of the Court – the moment in 2012 when the focus of the reform process, which had begun in Interlaken in 2010, shifted from technical reforms to enhance the Court’s efficiency to a concerted challenge to its very legitimacy and authority.

The turn to procedural review

For Judge Spano, the Court was “in the process of reformulating the substantive and procedural criteria that regulate the appropriate level of deference to be afforded to the Member States so as to implement a more robust and coherent concept of subsidiarity”. He dwelt especially on the 2013 Grand Chamber judgment in Animal Defenders International, which upheld by a tight (9-8) margin the UK’s ban on political advertising on broadcast media as a necessary interference with the right to free expression under Article 10 ECHR, even though this departed from its previous case law. The majority held (at para 108) that, when assessing the proportionality of a restrictive provision, “[t]he quality of the parliamentary and judicial review of the necessity of the measure is of particular importance … including to the operation of the relevant margin of appreciation”.

The dissenting judges in Animal Defenders International lamented what they saw as the application of a “double standard”, querying how a blanket ban could be considered proportionate just because the UK Parliament had found it so after debating the matter. Academic and civil society debate has reflected a similar range of concerns; for example, that the ECtHR is ill-placed to evaluate the quality of domestic (especially parliamentary) processes, or that an emphasis on process-based review might lead it to be too state-friendly, or that its case law risks becoming fractured between states that are seen to merit deference and those that are not.

A more robust concept of subsidiarity does not necessarily lead to an overly deferential approach. Scholars have coined phrases such as ‘active subsidiarity’ and ‘positive subsidiarity’ to capture the idea of galvanising domestic authorities to use the larger substantive interpretive space created for them by the ECtHR, based on the procedural qualities of their decision-making. As another former Court President Dean Spielmann ventured of the margin of appreciation doctrine, it is “neither a gift nor a concession, but more an incentive” to domestic decision-makers.

Message received and understood?

If the signal the Court wishes to transmit is that national institutions can “earn” deference through good faith human rights-based decision-making, are national institutions listening? In particular, does the “democracy-enhancing” thesis hold up with respect to how the UK Parliament and UK government have responded to the renewed emphasis on process-based review?

The Joint Committee on Human Rights (JCHR) was certainly listening and spelt out clearly the import of Protocol 15 which, inter alia, inserted references to subsidiarity and the margin of appreciation into the Preamble of the Convention. The JCHR drew Parliament’s attention to:

the increased onus the amendment to the Preamble places on the Court to pay respectful attention to the reasoned assessment of the national authorities, and, in turn, the correspondingly greater onus on, first, Government departments to conduct such detailed assessments of the Convention compatibility of their laws and policies and, second, Parliament to subject the Government’s assessment to careful scrutiny and debate.

JCHR, Protocol 15 to the European Convention on Human Rights (2014-15, HL 71, HC 837) para 3.18

The Committee noted that UK decision-makers have benefitted from the Court’s turn to process-based review, not only in Animal Defenders but also, for example, in judgments that endorsed the restriction on the right of British citizens resident overseas to vote in parliamentary elections and the prohibition of secondary strike action.

The UK government, too, is aware of the signals being sent from Strasbourg. Its consultation in 2022, Human Rights Act Reform: A Modern Bill of Rights, lauded the “age of subsidiarity” proclaimed by Judge Spano as having been “inspired by and negotiated under the UK’s stewardship”, adding that it creates “an opportunity to avail ourselves of this commitment to an increased margin of appreciation, and to make sure it is properly adhered to in the future”.

The Bill of Rights Bill – a backwards step

Regrettably, however, the government appears to wish to rely on the deference of the Court without taking the necessary steps to merit it – indeed, while taking what the Council of Europe and JCHR regard as a seriously regressive step through the Bill of Rights Bill (at the time of writing, still in parliamentary limbo). The Bill would undermine the UK’s constitutional ecosystem in various ways: not only would it require courts to defer to the government in numerous areas (analysed here and here), but it would also weaken legislative scrutiny.

Notably, the Bill would remove the requirement on ministers under s 19 HRA to attach statements of compatibility to Bills. In its response to the consultation on Human Rights Act Reform: A Modern Bill of Rights, the government said this was because the “stigma” attached to the making of a s 19(1)(b) statement acknowledging the risk of incompatibility “risks effectively operating as a veto on innovative policy making”.

This move was deplored by the JCHR in a letter to Dominic Raab in June 2022: its “very clear view is that these statements and explanations should be improved (not repealed) in order to facilitate meaningful parliamentary scrutiny”. Murray Hunt, Director of the Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law and former JCHR adviser, told the Committee that detailed human rights memoranda attached to Bills are crucial evidence of “conscientious consideration of ECHR compatibility issues” in the event of legal challenge.

The JCHR has made proposals to strengthen the s 19 process. These include ensuring that the obligation should bite upon introduction, rather than second reading, of a Bill, and that statements should be extended to cover compatibility with all applicable human rights standards. The Committee urged ministers to enable effective and timely human rights scrutiny, for example by addressing the problem of Bills proceeding to second reading at speed, sometimes with significant clauses arriving after introduction, and with inadequate explanations.

Such steps would be a concrete expression of the UK’s willingness to act on the signal inherent in the ECtHR’s turn to process-based review. Instead, the Bill of Rights Bill, and unceasing ministerial attacks on purportedly power-crazy judges in Strasbourg, embody a misconceived understanding of the Court. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that ministers know this but find it politically expedient to ignore it. The urgent interim measure that prevented the removal of asylum seekers to Rwanda is the latest lightning rod for this antipathy – and is unlikely to be the last.

Thanks to Professor Philip Leach and Anne-Katrin Speck for their very helpful comments on this blog.

Dr Alice Donald, Associate Professor, School of Law, Middlesex University

(Suggested citation: A. Donald, ‘Earning Deference from Strasbourg: Has the UK Got the Message?’, U.K. Const. L. Blog (6th December 2022) (available at https://ukconstitutionallaw.org/))