In the run up to the Scottish independence referendum, and its aftermath, calls have grown for a constitutional convention to discuss further devolution, as well as wider constitutional reforms. Yet most constitutional conventions around the world have failed to deliver subsequent reform. Careful thought therefore needs to be given to the purpose, scope and terms of reference, timetable, selection of members, budget, staffing and links to government and Parliament if a convention is to have any chance of success. Robert Hazell addresses each of these issues in turn.

Purpose

A constitutional convention is a group of people convened to draft a constitution (like the drafters of the American constitution in Philadelphia in 1787), or to consider specific constitutional reforms. In recent times conventions have come to include ordinary citizens, like the Irish Constitutional Convention which met from 2012 to 2014. A convention may be established for several reasons:

- To build cross party consensus for further constitutional reforms

- To harness expert opinion to chart a way forward

- To develop a more coherent overall reform package, rather than further piecemeal reforms

- To bring in ideas from outside the political elite

- To create greater legitimacy and support for the convention’s proposals

- To generate wider participation through innovative methods of public engagement.

A constitutional convention is not the only means of achieving these purposes. If the main objective is to build cross-party consensus, then cross-party talks are the obvious vehicle (as in the cross party talks which preceded the Belfast agreement, or the current talks on further devolution to Scotland led by Lord Smith of Kelvin). If the main objective is to harness expert opinion, then the best vehicle may be an expert commission. In recent years expert commissions have been successfully used to chart the way ahead for further devolution, with the Calman Commission in Scotland leading to the Scotland Act 2012, and a series of commissions leading to the grant of further legislative powers to Wales. But the extraordinary levels of public engagement during the referendum campaign in Scotland have created an expectation that for proposals to command legitimacy, there must be greater citizen involvement in producing them. The Scottish experience lies behind calls for a constitutional convention. But alternative models exist (for example, inter parliamentary talks); and there is no single model for a constitutional convention (see Alan Renwick’s excellent pamphlet, and Fournier et al’s book When citizens decide: Lessons from citizens’ assemblies on electoral reform OUP 2011).

Scope and terms of reference

One argument advanced for a constitutional convention is that it would enable development of a coherent overall reform package, rather than further piecemeal reforms. People have suggested that it should address the unfinished business from previous reforms: an elected House of Lords, a British bill of rights, reform of party funding, a written constitution. A list of reform proposals from all sides of the political spectrum could include the following:

- Renegotiating the balance of competences. In/Out referendum on EU

- Human rights. Repeal of the Human Rights Act. British bill of rights. Exit from ECHR, Council of Europe

- Reform of House of Lords. Further improvements to ‘transitional’ appointed House; directly elected second chamber; federal second chamber to represent nations and regions

- Reforms to House of Commons. Reducing size of House to 600. Changing the voting system. Votes at 16. Extending expatriate voting rights

- Reform of party funding

- A written constitution for the UK. This would offer the widest scope, encompassing all the above.

A convention charged with resolving such a wide range of different issues would face an impossible task. Each issue has proved intractable; in combination they are insuperable. Even if the convention is asked just to consider further devolution in the UK, the agenda would be sizeable. It includes the following items:

- Further devolution to Scotland, of tax and welfare. What else? Devo more or Devo max?

- Devolution finance, reform of the Barnett formula

- Further devolution to Wales (Silk report 2 on legislative powers)

- Further devolution to Northern Ireland (e.g. of corporation tax)

- Devolution within England: an English Parliament. Regional assemblies, city regions. Combined authorities, elected mayors, restructuring local government, reforming local government finance

- Rebalancing the Centre. English votes on English laws. Entrenching the devolution settlement. Combined Secretary of State for the Union. Federal second chamber.

This is a big agenda, and a convention charged with considering further devolution would need to have a phased work programme and prioritise certain items. Depending on the political context, it might decide to prioritise work on the English Question (see my earlier blogpost on The English Question).

Timetable

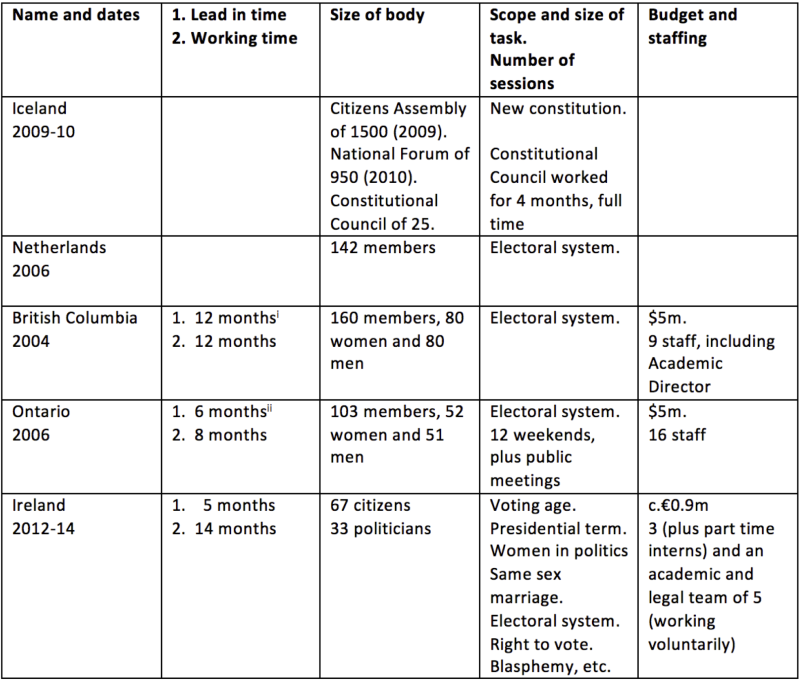

That brings us to the timetable. This must fit the agenda of the next UK government, and the wider political and electoral cycle. What results (if any) are required before the next UK general election in May 2015, the next Scottish elections in May 2016, the introduction of a British bill of rights, or a possible In/Out EU referendum in 2017? Practical realities mean it would be almost impossible to establish a convention before the May 2015 election. In other countries the lead in time required to set up a convention from the formal decision to establish one has typically been six months (see column 2 in the table below). Informal negotiations within the governing party and with other parties can extend that time further: in British Columbia and Ontario it took two years from the initial decision to establish an Assembly to the Assembly starting work. The table below shows the scope, timetable, budget and staffing of previous conventions. It is incomplete, and I would welcome help in filling the gaps and adding details of other conventions, but the data suggest that establishing a convention is a big and complex task, requiring careful planning with long lead in times.

Data about previous constitutional conventions

Once established, the timetable of a convention will depend on what it is asked to do. Three of the conventions listed above had a single task, devising a new electoral system. The Irish convention had eight tasks; the Icelandic convention a single huge task, creating a new constitution. The timetable will also depend on the size of the convention, and its working methods. The larger the convention, and the more participatory and inclusive its working methods (eg holding regional meetings), the longer it will take to complete its task.

Establishing the convention: membership, budget, and staffing

Much has already been written about the different options for selecting citizens to serve on a convention so that it is representative of all parts of the UK, and of gender, age, socio-economic background, ethnic minorities, disabled people etc (see Alan Renwick’s pamphlet and the Electoral Reform Society evidence). Ensuring adequate representation from all parts of the UK and all these different variables may result in a large convention: the Electoral Reform Society suggest 200-220 people. That in turn would require a large budget, for servicing large meetings, travel etc. The two Canadian conventions each cost $5m. The Irish convention cost only 1m euros, but was squeezed very tight: those involved say it needed twice the time and twice the money to do justice to its remit. In an age of austerity, with further cuts to come, a Rolls Royce convention may not be feasible. Proponents will need to think how far the size and cost can be scaled back without compromising the integrity of the exercise.

Even a scaled back convention is likely to cost low millions. If the government decides not to establish a convention, it is unlikely that anyone else could afford to do so. But it is conceivable that civil society organisations might try, through a large donation or innovative fund raising through crowdsourcing. They would then have to decide the terms of reference, the timetable, the membership, budget and staffing of the convention, and they would be responsible for the success or failure of the enterprise.

Working methods of the convention

Again, much has been written about this. The convention will need a strong online presence, with an excellent website, podcasts of all its sessions, and imaginative use of social media. It will need to commission and publish evidence, hold public meetings, and it may want to publish working papers and consultation papers. It will also need the ability to commission expert reports, to establish sub committees or expert committees, to commission polling data or other research. An expert panel can help to advise the convention, source and brief the relevant experts, and ensure it draws upon the widest possible research and evidence base.

Links to representative government and legislatures and the political process

Finally, the convention needs to maintain strong links with government and with Parliament to ensure that it carries them along with its thinking. Other conventions have failed in part because they have been too removed from the political process. One way of bringing the two together is to include politicians in the convention, as in Ireland where one third of the members were politicians, and two-thirds ordinary citizens (with mixed success, leading one adviser to suggest that any future convention might have only citizen members and a separate panel of parliamentarians as a conduit and sounding board). Another is to require the convention to deliver an interim report, and then to hold a parliamentary debate so that parliamentarians are informed of the convention’s thinking, and can feed back their initial reactions.

Conclusion

A constitutional convention sounds an attractive idea. But a convention established hastily, overloaded with too many tasks, inadequately staffed or required to report too quickly is almost certain to fail. That will be damaging to the cause of deliberative democracy as well as to constitutional reform. Those who call for a constitutional convention have focused almost exclusively on its membership, and how those members would be selected. As much thought needs to be given to its purpose, terms of reference, timetable, budget, leadership and staffing, as well as its links to government and Parliament. If equally careful thought and planning is given to all those things, a convention stands a much greater chance of success.

Robert Hazell is Professor of British Politics and Government & Director of the Constitution Unit.

This post originally appeared on the Constitution Unit Blog and is reposted with thanks.

Notes on Table 1

[i] The government that established the BC Citizens’ Assembly was elected in May 2001. It had promised an Assembly as part of a more ambitious reform package that included new public accounting standards, open cabinet meetings etc. There was some opposition in caucus to the idea of holding an Assembly, so it took time for the Premier to generate the necessary support. An expert, Gordon Gibson, was commissioned to prepare a plan for the Assembly, and reported in Dec 2002. In May 2003 the legislature endorsed the proposal, with amendments, and the government’s proposed chair. In August the selection process started with the first mailing of invitations. Selection meetings around the province went on over the fall and the Assembly was then ready to meet in January 2004.

[ii] It took 18 months from the Premier’s announcement of his intention to establish a Citizens’ Assembly, in November 2004, to the Regulation creating the Assembly and appointing the chair in March 2006. It then took a further six months to set up the Assembly, which started work in September 2006.