To many, ouster clauses represent a conflict between, on the one hand, the will of a sovereign Parliament and, on the other, the rule of law’s demands that public bodies act within the limits of their powers. The common law has traditionally sought to interpret ouster clauses restrictively, employing reasoning articulated classically (but far from the first time) in Anisminic Ltd v Foreign Compensation Commission [1969] 2 AC 147 and continued more recently in R (Privacy International) v Investigatory Powers Tribunal [2019] UKSC 22. That reasoning provides that ouster clauses do not apply where a public body has acted outside its jurisdiction: the “decision”, “determination”, etc (in the language of the clause) is null and void, such that there is nothing in law to which the clause might attach. The courts are thus able to safeguard the supervisory jurisdiction of the High Court while still claiming to pay due respect to Parliament’s decrees.

It has often been wondered what the courts would do if Parliament manifested in unambiguous terms its desire to exclude judicial review on these jurisdictional grounds. There were interesting dicta to this end in Privacy International, most especially from Lord Carnwath. His Lordship suggested (at [144]) that in cases of a truly irreconcilable conflict between Parliament’s express ouster of judicial review and the rule of law’s demands for the preservation of judicial oversight, there might be a “strong case for holding that, consistently with the rule of law, binding effect cannot be given to [such] a clause”. It was the court’s responsibility, he said, “to determine the level of scrutiny required by the rule of law”, even if this meant overriding parliamentary sovereignty.

Such an ouster clause appeared in clause 11 of the Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants etc) Bill 2003 but did not survive the parliamentary process. However, an express ouster clause has now appeared on the statute book. Section 2 of the Judicial Review and Courts Act 2022 introduces a new section 11A of the Tribunal, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007, aimed at reversing the Supreme Court’s decision in R (Cart) v Upper Tribunal [2011] UKSC 28 which permitted judicial review of appeals permission decisions by the Upper Tribunal where the second-tier appeals criteria were met. Notably, the clause was drafted in such a way as to circumvent a traditional Anisminic “reading down” of ouster clauses.

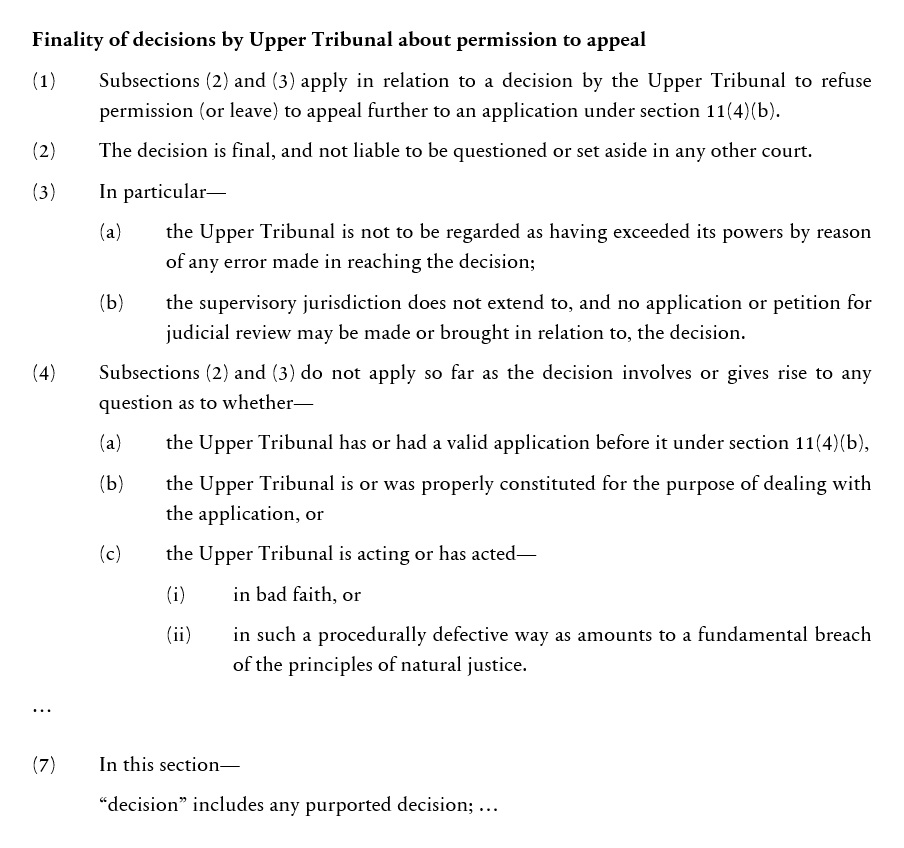

Section 11A says as follows:

Although subsection (2) speaks of “decisions” in the same way as any other ouster clause, subsection (3) specifies that errors committed in the making of a decision do not lead to the conclusion that the Upper Tribunal has exceeded its powers. As such, the attenuated conception of jurisdiction prominent in administrative law since Anisminic is prevented, limiting the courts’ interpretive powers to circumvent the clause. More importantly, subsection (7) makes clear that the reference in the clause to a “decision” specifically includes “any purported decision”, such that the ordinary Anisminic reading of an ouster clause cannot apply. The possibility of judicial review is preserved by subsection (4) only in cases of errors of jurisdiction in the limited pre-Anisminic sense (so-called “original jurisdiction”), as well as where the tribunal is improperly constituted, has acted in bad faith, or with procedural unfairness so grave that it constitutes a fundamental breach of the principles of natural justice.

In April of this year, section 11A fell for judicial consideration for the first time in R (Oceana) v Upper Tribunal [2023] EWHC 791 (Admin). The claimant, a citizen of the Philippines, had had her application for leave to remain refused by the Home Secretary. The First-tier Tribunal dismissed her appeal, and both the First-tier Tribunal and the Upper Tribunal refused permission for any further appeal. The claimant had sought to appeal the First-tier Tribunal’s decision on the basis that the judge had misunderstood her oral evidence. And in considering whether to allow an appeal, the Upper Tribunal judge had listened to the recording of the first hearing to check the veracity of the claimant’s claims, but without inviting the claimant to listen to the recording herself or to comment upon it. This, the claimant argued, was in breach of the principles of natural justice. She therefore sought judicial review of the Upper Tribunal’s refusal to allow an appeal.

The question thus arose as to what the court should do about the ouster clause in section 11A. Saini J considered two grounds of argument on this point. The first ground was whether the alleged procedural unfairness on the part of the Upper Tribunal constituted a fundamental breach of the principles of natural justice, such that the exception to section 11A’s ouster of judicial review in sub-section 4(c)(ii) applied. Saini J found this argument unconvincing, rejecting the contention that the Upper Tribunal had acted in a procedurally unfair manner ([33]).

Attention then turned to a second ground for judicial review. The precise nature of this ground is not clear, but it seems the claimant was arguing that the Upper Tribunal had erred in law by deciding that potential evidential misunderstandings by the lower tribunal were insufficiently important to justify an appeal. But by relying on what appears to be an argument as to an ordinary error of law committed by the Upper Tribunal, and therefore coming up hard against the ouster clause in section 11A, the claimant was required to advance what Saini J described (at [46]) as an “ambitious submission” that the courts had the power at common law to ignore what was agreed to be a clear statutory exclusion of judicial review.

Saini J rejected this submission as well, pouring cold water on the idea that dicta in Privacy International allowed him to take a more liberal approach. To quote Saini J in full (at [52]):

Putting aside obiter observations in certain cases and academic commentaries, in my judgment, the legal position under the law of England and Wales is clear and well-established. The starting point is that the courts must always be the authoritative interpreters of all legislation including ouster clauses. That is a fundamental requirement of the rule of law and the courts jealously guard this role. However, the rule of law applies as much to the courts as it does to anyone else. That means that under, our constitutional system, effect must be given to Parliament’s will expressed in legislation. In the absence of a written constitution capable of serving as some form of “higher” law, the status of legislation as the ultimate source of law is the foundation of democracy in the United Kingdom. The most fundamental rule of our constitutional law is that the Crown in Parliament is sovereign and that legislation enacted by the Crown with the consent of both Houses of Parliament is supreme. The common law supervisory jurisdiction of the High Court enjoys no immunity from those principles when clear legislative language is used, and Parliament has expressly confronted the issue of exclusion of judicial review, as was the case with section 11A.

The High Court’s decision in Oceana is unlikely to be the last word on the matter. Nonetheless, the case raises important points of constitutional law. Saini J’s statement that the rule of law is a principle applicable to all constitutional actors equally, the courts as much as Parliament and the executive, is important: Parliament also has a role in determining the requirements of the rule of law; the courts also have a duty to abide by the rule of law’s demands. But more important is Saini J’s reminder that parliamentary sovereignty is still the constitutional norm sine qua non of the UK’s constitution. As such, judicially discerned requirements of the rule of law must ultimately yield to that more fundamental norm. Sometimes, it seems, this will entail effect being given to express ouster clauses. And in such cases, it is for Parliament to accept the full moral and political consequences of promulgating them.

Philip Murray is a former Fellow and College Lecturer in Law at St John’s College, Cambridge. He can be emailed at philip.murray@cantab.net.

(Suggested citation: P. Murray, ‘Reconsidering Ouster Clauses: The High Court’s Decision in Oceana’, U.K. Const. L. Blog (5th July 2023) (available at https://ukconstitutionallaw.org/))