The resurrected Bill of Rights Bill (BoRB) shows that the government is continuing to grasp at the wrong end of the remedies stick – and it will continue to do so until it pays attention to the evidence.

The resurrected Bill of Rights Bill (BoRB) shows that the government is continuing to grasp at the wrong end of the remedies stick – and it will continue to do so until it pays attention to the evidence.

In its 2019 Manifesto, the government made a lofty commitment to restructuring the fundamental relationship between the three branches of the state. Instead, it has resorted to what is becoming a pattern of unnecessary remedial reform. This reform is unnecessary for two reasons. Firstly, it fails to grasp the real problem with the judicial exercise of remedial discretion. Secondly, it presumes that the problem is best resolved by legislation.

The quashing of statutory instruments (SIs) by the courts was a particular target of both the government and the body of thought from which many of its reform proposals originated. I tested the assertion that quashing “impeded effective government” by examining 122 judicial review challenges against SIs in England and Wales from 2014 to 2022 to see how many of these resulted in either quashing the SI or a declaration; how many involved human rights; and how many found in favour of claimants.

This piece identifies two major trends in the outcome of successful judicial reviews and why additional legislative reform of remedies may be futile. Firstly, I argue that the Government’s reform agenda is misguided as the real problem lies in the underuse of quashing as a remedy for SI cases. Secondly, in the context of declaratory relief, I argue that the reforms in the BoRB fall short of their intended purpose due to a lack of understanding about how the courts approach declarations.

It is easy to lose sight of remedies in flashier public law debates. For individual claimants, however, remedies breathe life into access to justice by ensuring that something tangible arises out of their arduous engagement with the court process. Meaningful change in this area would require the courts to resituate remedies to the centre of the rule of law, and the government to grant breathing space to enable judicial action.

Quashing orders

The settling dust of the Judicial Review and Courts Act 2022 (JRCA) reveals that the overall impact of the last two years of reform talk on remedial discretion has been modest. Section 1 of the JRCA enables judges to suspend or make prospective-only quashing orders. The Government agreed to drop the presumption in favour of suspended quashing in the initial Bill. It has been confirmed that the provisions relating to suspended and prospective quashing orders will also apply to proceedings under the BoRB. Moreover, the BoRB preserves the ability of courts to quash secondary legislation for violations of rights contained in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

The limited scope of the reform to quashing is welcome, particularly where it preserves the discretion of the courts to grant relief on a flexible basis. Nonetheless, the data I have collected gives rise to two ongoing concerns, one about the process of reform and the other about its substance.

The first of these relates to the weak evidential basis on which the Government is willing to undertake resource- and time-consuming reform programmes. While discussions about suspended and prospective quashing in both the post-Independent Review of Administrative Law (IRAL)

and post-Independent Human Rights Act Review (IHRAR) consultations were framed as tackling the quashing of secondary legislation, this was an area in which quashing rarely came into play.

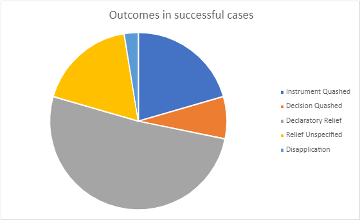

Though studies of judicial review remedies in general have found that quashing was the most frequently issued form of relief, the data below shows a different pattern where SIs are challenged. Here, the courts ordered quashing in only eight cases – a quarter of all judgments that found against the validity of SIs. Four of these were orders quashing individual decisions that had been made under the SI being challenged. At final instance therefore, eight SIs have been quashed in over eight years, and none since January 2020 (the last quashing recorded in a judgment as of June 2022).

The lack of evidential basis for reforming remedies forms part of a broader trend highlighted elsewhere in relation to the Human Rights Act consultation. Not only does this constitute poor policymaking practice, but it also means that already scarce parliamentary time is occupied by reform agendas that, at best, merely codify the existing state of the law (it has been acknowledged by the Government and argued elsewhere that there already exists precedent for granting suspended and prospective quashing orders).

At worst, they introduce undue complexity into the law. This complexity not only constrains individuals’ ability to vindicate their rights, but it also leads to more litigation when the courts are called on to interpret new legislation.

Secondly, the problem is not, as suggested by proposals to limit the use of (retrospective) quashing, that courts are excessively quashing, but that they quash SIs so rarely. Quashing is an important feature of the remedial toolkit as it has the effect of setting aside an unlawful action or instrument and depriving it of any legal effect, both retrospectively and prospectively. Quashing orders can be criticised, when bringing an end to administrative schemes and policies, for the abruptness of their effect and the legal uncertainty they are said to generate in the time it takes to reformulate and replace the impugned measures. The courts should be and have been alive to both the public and third-party interests at play when considering the quashing of SIs; however, while a cautious approach appears to respect the rule of law and its requirements of legal certainty, excessive wariness may undermine an equally fundamental aspect of that principle.

This was elaborated in R(C) v The Secretary of State for Justice, where Buxton LJ at [41] rejected the notion that delegated legislation should be treated as exceptional through an exemption from quashing. Instead, he found that the rule of law and the:

imperative that public life should be conducted lawfully suggests that it is more important to correct unlawful legislation, that until quashed is universally binding and used by the public as a guide to conduct, than it is to correct a single decision, that affects only a limited range of people.

On this subject, the Supreme Court more recently restated that the courts ordinarily refrain from making coercive orders, that is, orders that go beyond declarations by striking down administrative acts or mandating that the government take specific action, in the “clear expectation that the executive will comply with a declaratory order” [44]. This statement is based on the constitutional principle of mutual trust between the courts and the Government.

However, it arguably only holds weight when both sides demonstrate equal respect for the rule of law. The actions of the government suggest that it does not always value good faith compliance with its legal obligations, nor does it welcome judicial oversight, whether domestic or international. The mutual trust principle should be tempered by a stronger-handed approach to remedies, particularly where an SI is found to have breached fundamental rights.

Declaratory relief

There are two mechanisms through which a court can “declare” an SI incompatible with human rights. The first is a traditional declaration of unlawfulness under Section 31(2) of the Senior Courts Act 1981 (SCA), and the second is a declaration of incompatibility under Section 4(4) of the HRA.

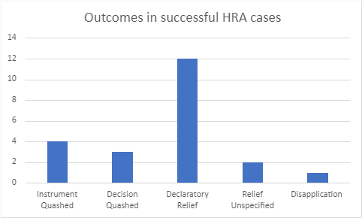

Declarations are by far the most commonly granted form of relief. Over half of all successful challenges to secondary legislation resulted in a declaration and 60% of these were granted in HRA claims. The vast majority of these were declarations under Section 31(2) of the SCA to the effect that the SI was unlawful in light of a given ECHR right. Only one case at final instance in the dataset resulted in a Section 4 HRA declaration of incompatibility (DOI).

Although more often discussed in the context of primary legislation, Section 4(4) HRA also allows the courts to grant DOIs when secondary legislation is challenged. The conditions that must be met are that firstly, the provision is incompatible with an ECHR right, and secondly, the parent Act of the SI prevents the removal of the incompatibility. Clause 10 BoRB reflects the government’s view that “reform is needed to give courts a wider ability to declare secondary legislation incompatible”. To this end, it removes the second requirement of Section 4(4). Presumably, the intended effect of this removal is twofold: it compels courts to issue more DOIs by leading the courts away from ‘expansive’ statutory interpretation.

This would be in line with Clause 3 BoRB, which repeals the interpretive duty in Section 3 HRA. Section 3 obliges the courts to interpret domestic legislation compatibly with ECHR rights so far as possible. The Government has argued that this duty has led to the courts adopting overly broad interpretations of legislation and “straightforward judicial amendment”. Therefore, Clause 3(2) BoRB mandates a stricter textual approach to interpretation, and 3(3) limits the ability of the courts to expand the “protection conferred by the right”. Elliott has predicted that removing the Section 3 obligation will lead to an increase in the number of declarations of incompatibility issued and a weakening of the force behind the declarations.

However, this assumes that the effect of repealing Section 3 would be the same in relation to judicial review of both secondary legislation and primary legislation. There are various reasons why DOIs have been underused so far (a recent post explores the judicial reluctance around DOIs in the primary legislation context). In relation to SI challenges only, I offer three reasons as to why the attempt to force courts to grant more DOIs may not pan out as expected.

The first is that currently, in order to grant a Section 4 declaration, the courts must have reached the limits of interpretation under Section 3 HRA. However, in cases arguing HRA grounds, the courts may still be using the ordinary rules of construction instead of the Section 3 interpretative approach. There is an unfortunate lack of clarity and consistency about the interpretive methods applied in HRA cases, particularly when common law grounds are also being argued. This was also highlighted by the Independent Human Rights Act Review, which suggested that a database tracking the use of Section 3 would help identify any serious concerns about the interpretive method. In the absence of such data, the prevalence of SCA 1981 declarations over DOIs may suggest that Section 3 is not being used as frequently as assumed. Consequently, the Government’s emphasis on DOIs is unlikely to achieve anything that the courts are not already relying on common law interpretation for.

The second reason is that the quiet force of SCA 1981 declarations may be preferred by the courts to the noise of DOIs. Traditionally, DOIs have been seen by the courts as a harsh and last-measure action, even though they have “only political, not legal, implications”. Lord Reed in the UNCRC case went so far as to describe the enactment of Section 4 HRA by Parliament as a self-imposed qualification of its sovereignty [50]. While the reluctance towards granting DOIs, at least in the current Supreme Court, may be in part explained by that body’s deferential turn, the underuse of DOIs predates this trend, suggesting that the judicial calculation of remedial effectiveness has weighed in favour of SCA 1981 declarations for a while.

The Supreme Court in Craig v HM Advocate was clear that the Government is expected to comply with (ordinary) declaratory orders, even if just as a matter of constitutional principle. In contrast, the Government is not obliged to address incompatibilities under Section 4. It is therefore possible that the courts have been reluctant to issue DOIs because the constitutional principle of mutual trust that required the Government to comply with ordinary declaratory orders does not apply to the Section 4 scheme. Although the Government reports that all DOIs made since the HRA came into force have been acted upon, there may be a latent judicial suspicion that this is at least in part due to the low number of DOIs. Indeed, it seems unlikely that the Government is pushing for the increased use of DOIs in SI cases with the intention of acting diligently upon each declaration. Ordinary declarations may therefore protect the institutional and cultural authority of the courts in a way that DOIs, if granted and ignored on a large scale, may threaten.

Thirdly, a more informal reason may be the reluctance of claimants and counsel to request DOIs. It may well be that the reticence of claimants and the reluctance of the courts trap the two into a cycle. If the courts are perceived to be hostile to DOIs, claimants might not request them, and because claimants have not requested them, the courts might see no need to go beyond the relief asked for by granting DOIs and triggering the Section 4 mechanism.

This problem may be exacerbated by a lack of transparency in the practice of granting relief. The data shows that in approximately a quarter of successful judgments, the court either concluded by inviting the parties to make submissions on relief (without including the final order), or without any reference to remedies at all. Other studies have confirmed that the nature of relief granted, if any, in the event of a successful challenge could not be discerned in a number of cases. “Transparency and consistency in judicial reasoning about remedies” could help ensure that individuals are not deterred from demanding the form of relief most effective in remedying the suffered breach of right due to a lack of consistent precedent on the granting of that remedy.

While the lack of justification for reforming remedies is concerning, this piece has argued that the recent reforms are unlikely to have a significant effect on the practice of granting relief. The ball is currently in the judiciary’s court to take the initiative to develop a clear and reasoned approach to the granting of remedies.

Conclusion

Remedies have been a hot topic in the Government’s discussions of reform, but seemingly for all the wrong reasons. Evidence has shown that fears about the courts abusing remedial discretion to undermine executive action, particularly in relation to SIs, simply fail to be substantiated.

This does not, however, mean that all is well with remedies. If anything, the courts have shown a reluctance to make proper use of their remedial discretion in shying away from granting strong forms of relief. The potential rule of law and access to justice implications mean that there are consequences of this approach for more than just the individual claimants in any given case. Like any discretionary power, the flexibility of the courts in granting relief comes with the duty of responsible exercise.

Recent reforms have been costly, time consuming and evidentially lacking for which the Government should rightly be criticised; however, they may hopefully bring to the attention of the courts the need to ensure that the law of remedies in judicial review is not further complicated by the courts themselves.

Saba Shakil is a Research Assistant at the Public Law Project.

(Suggested citation: S. Shakil, ‘Bridging the gap between remedial reform and judicial practice: A study of challenges to delegated legislation ’, U.K. Const. L. Blog (24th November 2022) (available at https://ukconstitutionallaw.org/))